Farmers as National Symbols: From American Cowboys to Armenian Shepherds

Across the world, the figure of the farmer, herder, or rancher has often risen above daily labor to become a national symbol of identity, resilience, and freedom. From the sweeping plains of America to the high pastures of Armenia, societies have celebrated those who live closest to the land as guardians of culture and tradition.

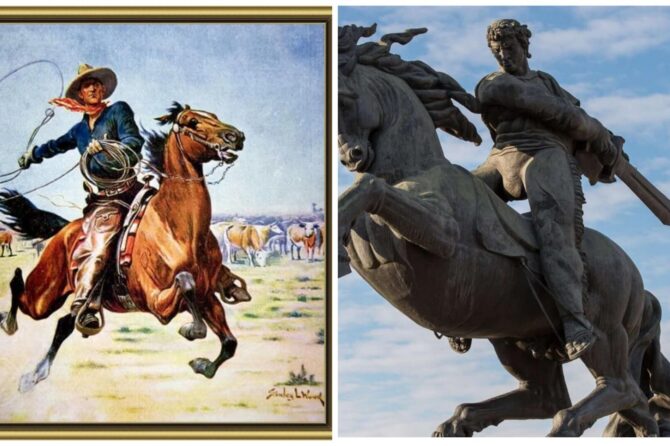

The Cowboy of the American West

In the United States, no figure is as instantly recognizable as the cowboy. Emerging from the cattle trails of the 19th century, cowboys came to embody freedom, toughness, and the romance of the frontier. Songs, novels, films, and even modern rodeos have kept the cowboy alive as a cultural symbol, representing both the independence and the rugged individualism America admires.

The Gaucho of South America

In Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil, the gaucho holds similar status. Known for their horsemanship, cattle-ranching skills, and distinctive poncho and knife (facón), gauchos became legendary in South American poetry, music, and folklore. They represent not just cattlemen, but also the soul of the pampas — proud, free, and deeply tied to the land.

Europe’s Rural Icons

While Europe industrialized earlier than much of the world, it too treasures the figures of shepherds and farmers who shaped its landscapes.

- Switzerland: The alpine Senn (dairyman and cowherd) is a deeply symbolic figure. Each summer, herders lead cows to high mountain pastures in the Alpabzug or Almabtrieb — the festive “descent of cattle” in autumn, celebrated with decorated cows, bells, music, and costumes. Swiss folklore also venerates William Tell, the legendary farmer-archer who stood for freedom, showing how rural life and independence are woven together in the Swiss identity.

- Spain: Beyond matadors, Spain honors the pastores (shepherds) of Castile and the Basque highlands, whose transhumance (moving flocks seasonally) shaped landscapes for centuries. Romantic poetry and festivals preserve their cultural place.

- Italy: The contadino (peasant-farmer) and the buttero (Tuscan cattle herder, akin to a cowboy) symbolize the rural roots of Italy. The butteri, still practicing in the Maremma region, ride horses and manage cattle much like gauchos or cowboys.

- France: The paysan has long been seen as the backbone of the nation. In regions like Provence and the Pyrenees, shepherds and cheesemakers are celebrated in songs and festivals. The berger (shepherd) is especially romanticized in French pastoral art and poetry.

- Norway & the Nordics: The seter girls (milkmaids) and mountain shepherds who tended summer farms (seterdrift) are remembered in folk songs, traditions, and even tourism. They embody a simple, pure connection to nature.

- Russia: The Peasant as the Nation’s Heart: In Russia, the mujik (peasant farmer) has long symbolized the soul of the nation. In literature from Tolstoy to Nekrasov, peasants are depicted as strong, enduring, and spiritually deep, even in hardship. Russian songs, proverbs, and art often elevate the simple farmer to the role of cultural hero — the one who feeds the land and carries its traditions forward.

Armenia: The Shepherd of the Mountains

Armenia’s rugged highlands have always been home to shepherds and farmers, and its national art reflects their importance.

In Armenia, the central hero of Armenia’s national epic, David of Sasun, is remembered as a shepherd. He was not only the defender of the mountains and a warrior against enemies, but also the master of the land and the flock. David embodies the idea that the Armenian hero draws his strength from caring for the land and the herd. From this deep rural root came his power. David of Sasun thus stands not only as a freedom fighter, but also as a heroic symbol of the farmer-shepherd tradition.

In addition, Armenian pastoral and agricultural life has always been a defining feature of the highlands. The national opera “Anoush” (by Armen Tigranyan) glorifies the shepherd through its main hero, Saro. Saro is not only a tragic romantic figure, but also the symbolic archetype of the Armenian shepherd — free, proud, and deeply tied to the mountains.

Armenian folk songs, poetry, and dances also often praise the shepherd, the flock, and the high pastures. Just as the cowboy embodies the American West, the shepherd embodies Armenia’s deep bond with its highland soil and traditions.

A Universal Romance with the Land

Though the cowboy and gaucho may be the most internationally famous, almost every nation has its own farmer-hero, a figure elevated from laborer to legend. They symbolize not only the food and livelihood they provide, but also freedom, connection to the nature, resilience and endurance, cultural continuity.

In celebrating these figures, nations celebrate more than farming. They honor the human spirit rooted in the soil, resilient against hardship, and free beneath the open sky.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply